Phi Beta Kappa Members Liberate Minds in Mississippi Prisons

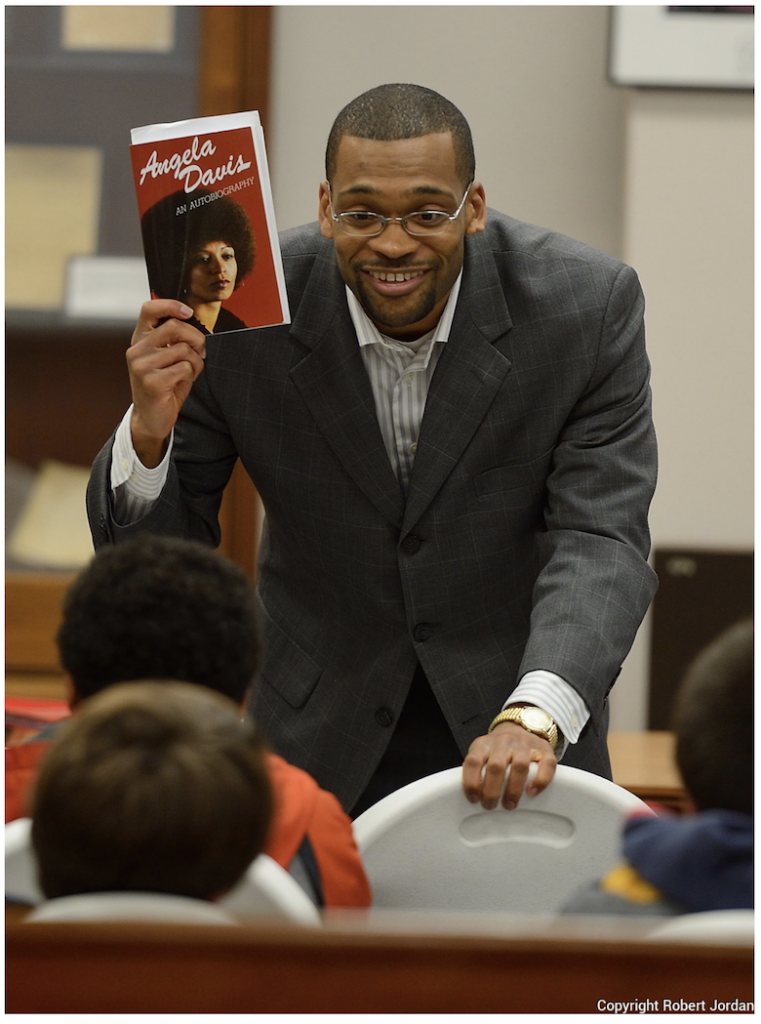

Patrick Alexander talks about the work of Angelia Davis and her use of ‘up words’. Photo by Robert Jordan/UM Communications

FEBRUARY 3, 2020 BY JACQUELINE KNIRNSCHILD

In the office of University of Mississippi English and African American Studies professor Patrick Alexander, there is a framed photo of him shaking Angela Davis’s hand in 2012. Alexander’s bookshelves are filled with titles like Malcom X: The End of White World Supremacy, A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest Gaines and Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Alexander, who is a member of Phi Beta Kappa, attended grad school at Duke University, where he founded an award-winning academic enrichment program for imprisoned students, and where he met renowned scholar, anti-prison activist and former political prisoner Angela Davis, who is also a member of Phi Beta Kappa.

Davis went to Duke to give a lecture about social justice and her own experiences spending eighteen months in jail and on trial in the early seventies. Davis is the author of over ten books, including Are Prisons Obsolete? which Alexander said he’s read at least thirty times. Davis’s scholarship urges Americans to think seriously about a future without prisons, because prison “relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.” Davis and Alexander argue that building communities and social institutions which prioritize the economic, educational and psychological needs of all citizens will make prisons obsolete.

“She’s very engaging,” Alexander said about Davis. “She really wants to create action, not just give an address.” Before the photo was taken, Alexander and Davis were discussing methods of teaching in a way that honors incarcerated students’ humanity. Alexander asked Davis to sign a copy of her autobiography for his students and Davis signed it, to my brothers with love. “That is now permanently part of the library at Orange Correctional Center in Hillsborough, North Carolina,” Alexander said. “It was amazing to see her investment in them.”

Alexander came to the University of Mississippi in 2012 and during his faculty orientation, the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts Dr. Glenn Hopkins called his name out in front of the 82 new professors and said that if you like money and want to teach incarcerated people, the university has opportunities for you. After the orientation, Alexander, Hopkins and Dr. Otis Pickett discussed starting an academic program in prisons and Hopkins told them, “you all are the leaders—you guys put something together and know that the money is here.” At Duke, Alexander was working and fundraising all the money for the Stepping Stones program on his own, so, having University of Mississippi support from day one made things a lot easier and opened the door for the program to expand quickly in just a few years. “My first day on the job was amazing,” Alexander said. “I knew this was the kind of university I wanted to work for.”

After spending a year just visiting the Mississippi State Penitentiary, Parchman Farm, to see what the needs were, Alexander and Otis founded the Prison-to-College Pipeline Program in 2014. PTCPP offers for-credit college courses in subjects which imprisoned students are interested in. UM English faculty teach the same classes at Parchman that they would teach on campus, such as Eng 324: Shakespeare and Eng 362: African American Lit Survey Since 1920. Yet, PTCPP courses are also designed specifically to cater to incarcerated people. “We articulate to students that we know this is not our turf and if there’s ways we can tailor course material to their curiosities and their needs, we’ll do that.” Alexander’s said they do course inventories and found that many imprisoned students want to learn about the things they didn’t learn in high school, like Fannie Lou Hamer, Ida B. Wells, Richard Wright. And with the University as the primary funder, in 2016, PTCPP was able to expand to provide higher education to the incarcerated women in the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Jackson.

Alexander said he thinks there is so much openness about mass incarceration and prison reform in Mississippi because the issue is so egregious here, with Mississippi having the third highest incarceration rate, behind Oklahoma and Louisiana. “There’s so many human rights abuses and lack of college education here so there were a lot of open doors.” And in the past few weeks, issues with Mississippi’s prison system have become national news with the deaths of now fourteen inmates and leaked photos taken on inmates’ phones revealing inhumane conditions of mold, clogged drains, exposed wires and broken toilets at Parchman. Hundreds of people gathered in front of the Capitol building in Jackson on January 24th to demand prison reform.

One of the goals of the PTCPP is to reduce recidivism rates, meaning to reduce the tendency of a released criminals to reoffend and wind up back in prison. But Alexander said that reducing recidivism is just skimming the surface of prison reform. “Recidivism is a sneeze that points to a larger disease.” The underlying issue, Alexander said, is that imprisoned people are not treated as human-beings. Alexander contends that the current explosion of troubles with Mississippi prisons is not a “crisis” but rather, a reflection of “the lack of investment in the fundamental humanity of people who are incarcerated,” which arises from the Western idea that there must always be an “other.” He pointed to a photo of prisoners at Parchman in 1901 wearing stripes and a photo from 2014 of prisoners wearing the exact same stripes in a PTCPP class.

Mass incarceration is the disturbing but logical outcome of institutional forms of white supremacy that we haven’t dealt with as a society yet, Alexander said. The United States remains the indisputable world leader in imprisonment with well over two million of its people in prisons and a 408 percent increase in prison population over the past four decades, Alexander writes in a 2018 special report. Mass incarceration is tethered in slavery and the infamous exception clause in the Thirteenth Amendment, which states, “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist with the United States,” meaning imprisonment functions as a method of racialized social control that is reminiscent of slavery.

For the Lift Every Voice Celebration, which honors the black national anthem, Alexander will be giving a talk on Monday, February 3rd at 4pm in the UM Student Union ballroom. Alexander said he will encourage students to get involved and be inquisitive because there is a lot going on in this state. “It’s a beautiful, terrible thing,” Alexander said. “There’s so many bad things that are happening, but it also has spawned a lot of organizing activity and I think that young people can and should be at the vanguard.”

Dr. Fisher-Wirth (middle) and Dr. Alexander (right) with students in the UM Prison-to-College Pipeline Program.

Students have opportunities to volunteer with the Mississippi Innocence project, which is dedicated to exonerating the wrongfully convicted, and the Mississippi Freedom Letters campaign, which aims to write a letter to every inmate in the state in order to send love and support. Students can also get involved with the Equal Justice Initiative, Southern Poverty Law Center and the American Civil Liberties Union. And in December, the University hosted the national Making and Unmaking of Mass Incarceration conference, which explored the future of prison abolition and what is being done to reduce society’s reliance on prisons and other punitive solutions. Activists, community leaders, students and scholars from around the country attended this conference, including Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who co-founded Critical Resistance with Angela Davis in 1997, which is a grassroots organization that works to dismantle the prison-industrial complex.

“Coalitional formations that link academic communities and imprisoned communities can potentially produce great changes,” Angela Davis stated in her 1997 speech, which greatly inspired Alexander’s teaching of African American literature in prisons. “We often fail to recognize that prisoners are human beings who have a right to participate in transformative projects.” Prison abolition involves crowding out existing prison system with new institutions that address the social problems that brought people to prisons in the first place, Alexander said. New institutions include improved public education, mental health services and addiction rehabilitation. Davis also writes that radical opposition to the global prison-industrial complex involves building relationships—genuine solidarity—with the men, women and children behind bars. Davis’s ideas about genuine solidarity have inspired Alexander to cultivate classrooms where imprisoned people can, if only temporarily, “experience human community amid ever more extreme forms of social isolation.”

It’s also important not to come into prisons with a white savior complex, Alexander said, because volunteers and teachers often come away having learned so much than what they gave out. Alexander points out that engaging with imprisoned peoples has led to many literary discoveries, for example, Toni Morrison’s book Beloved was heavily informed by Angela Davis’s books. Morrison was a longtime editor at Penguin Random House, so she edited Angela Davis’s autobiography and got first-hand perspective on what life was like in women’s’ jails. “I looked back and did the research and careful reading,” Alexander said. “And it’s clear to me that Angela Davis has improved the genius of Toni Morrison.

During the fall semester of 2016, Alexander team-taught a hybrid African American literature and creative writing course with English professor and Phi Beta Kappa member Ann Fisher-Wirth at Parchman. “It was really one of the high-points of my teaching career,” Fisher-Wirth said. “I learned more than I taught.” Fisher-Wirth published the eleven imprisoned students’ creative writing in a special portfolio for literary journal About Place. In the introduction of the issue, titled South, Fisher-Wirth writes, “These Wednesday afternoons combated the ‘soul death’ of incarceration with the soul depth of beauty and truth and imagination.” In a piece titled The Astonishing Light, Fisher-Wirth writes about how Alexander told their students, “Sometimes you can’t change the confinement of your body, but you can free yourself from the confinement of your mind.” Alexander also began every class with the chant, “I’M A STUDENT! I’M A TEACHER! I’M A SCHOLAR! I’M CREATIVE!” Fisher-Wirth writes that they all shouted the chant three or four times together and she loved how the affirmation revved up the men to whom life has offered little.

In Fisher-Wirth’s segment of the class, students wrote about “romance, babies, football, grandmas or aunties who raised them and pray for them, cousins who died from guns, uncles who taught them how to hunt and found them when they got lost in the woods.” In another essay, for Terrain Magazine, titled Letter to America, Fisher-Wirth writes that her students’ writings showed her that “the conditions of their lives only partly define them.” The students’ work made her proud. “They have been men of courage, intelligence, good will, humor and yes, unabashed gratitude and wholehearted love.”

“I’m not suppose to be here in the first place / Not in a world that teaches you to love, but hate you,” Brendell Williams, from Columbus, Mississippi writes in his poem Stillborn. “I’m suppose to be still, enjoying silence, knowing no pain, no stress / I’m suppose to be there, not here, but yet… / I wrecked the car totally, I overdose on drugs / I fought more than ten at one time… I’m not / suppose to be here, but my reason, I didn’t know, until now… / I was sent to write a poem, and give it to workshop.” In his writer bio, Williams writes that he is delighted to share his first publication and urges readers to keep pushing in life. “My future plan is to become successful in music, writing and ownership of a successful business,” Brendell writes. “I dream big because I’m a scholar, a student, a teacher, and I’m capable.”